Shana Fife se memoir virrie benefit van Coloured women

Ougat: Sy is glattie op haa bek gevallie

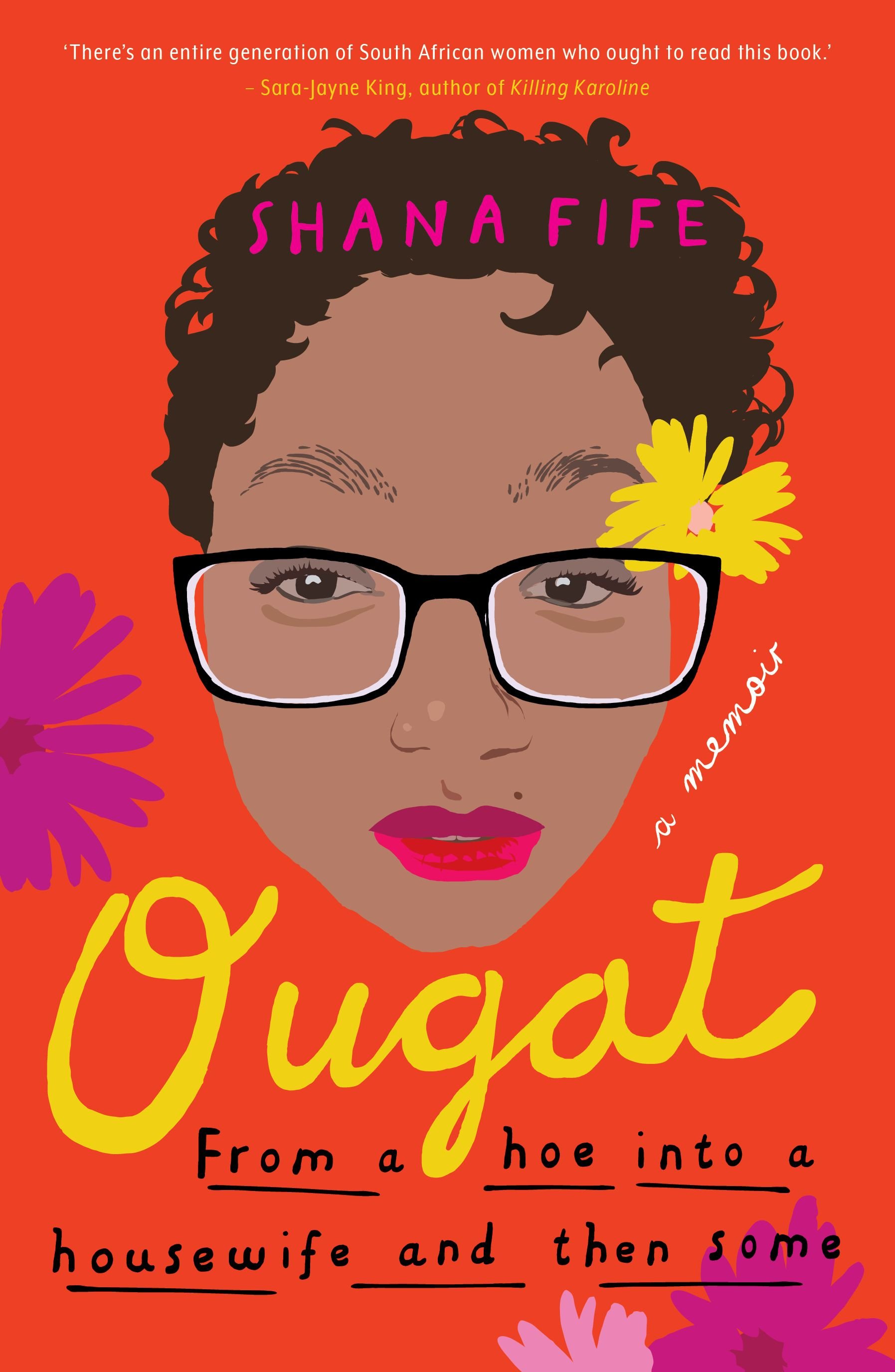

Shana Fife se memoir Ougat: From a hoe into a housewife and then some wôd beskryf as ’n skok virrie system deu Bronwyn Davids, skrywer van Lansdowne Dearest (2020). Shana se stem wôd verder deu Sara-Jayne King, die skrywer van Killing Karoline (2017), beskryf as ’n belangrike een innie collective journey van vroue van kleur wat oppie road na healing en die acceptance van hulself is.

Ougat is in 2021 ge-publish deu Jonathan Ball Publishers. Ek is particularly interested innie boek omdat ek verskriklik nosy is en equally altyd in spaces beweeg waar die untold narratives reside soes tussen bergies oppie straat, prossies in Long Street en kos innie koskassies van ouma-goed. Ougat is Shana se debut book, maa sy praat soes een wat al vi jare sit en bek vekoep; gemaklik, eerlik, met not a care in the world. Ougat is ’n brutally honest storie oor survival — surviving sexually met al die inherited, imposed en uninvited trauma, mentally met depression, socially mettie conditioning wat aan die heup hang vannie Cape Flats soes ’n baba met ’n nat nappie, en die escape vannie wrede cycle van abuse. Dis ’n boek wat my excite, want finally praat iemand oor taboo topics wat almal wiet bestaan, maar niemand regtig te ver weg vannie huis af bespreek nie.

Ek gesels met Shana for all things ougat, life, die balancing act van writing your truth and then some.

I am Coloured. I am woman.

Both of those titles have infinite interpretations. As much as this memoir is about my sexual identity as a Coloured woman and the things I had to endure as a sexually aware person living in a very anti-sex, yet sex-driven culture, it is important to take into consideration all the other factors and seemingly unrelated experiences that merged to create my persona. [Hoofstuk 4, ‘…and women’]

VERONIQUE: Shana, jou memoir is raw en befok. Wat wassie creation process like? Was jou intention vannie get-go af ’n memoir of het jy getokkel met ideas van ander genres?

Shana Fife

Foto verskaf

SHANA: Thank you! Creating Ougat was smooth sailing until I had to read it to edit the second draft. I got physically sick and my muscles seized up — had me bedridden for a week. I wrote it at the beginning of the pandemic in hard lockdown, so I was grateful to be able to just sit and write and not have an excuse to go somewhere. My whole family was in the house and to be honest, going to my desk and closing the door to write was a lekker excuse to leave my kids with my husband for a few hours and escape the chaos that was level 5.

As for intentionally writing a memoir, Jonathan Ball editor at the time, Aimee Carelse actually approached me while I was writing a different, fictional piece (also a book aimed at a Coloured audience). She asked me specifically if a memoir interested me — and it felt serendipitous. Before I met her, I was known for blogging about my life experiences and abuse, but it was all occurrences from the surface and not a deep dive into the WHY. Ougat is the culmination of all those stories.

VERONIQUE: Innie begin vannie note wat jy gie, noem jy: “Events in this memoir are based on my understanding and interpretation of them at the time.” Ek love dat jy vannie begin af sommer ownership vat vannie ship en sodoende die unnecessary diluted responses uit die pad uit stoot. Was daai intentional? Ek wiet dit maak altyd die storievertel proses vi my makliker op daai manier.

SHANA: It actually wasn’t in the first print run. And I should have known better and put it in there. When my extended family read it, they were upset about the story I told about my aunty Brenda. It was then I realised that we all remember the same events from our own, sometimes differing perspectives. I felt like I owed her, and the audience, my acknowledgement of the fact that I am not the authority on “how things really went”. That said, everything was authentically as my young brain saw and absorbed it — I just respect the way others interpreted it.

VERONIQUE: Het jy ’n ideal reader in mind gehad terwyl jy geskryf het?Jy het eers jou stories vertel en experiences gedeel op jou blog en reach nou ’n larger audience deur die boek. Voel jy die gesprek het gegroei tot jou ideal target audience, as iets soes ’n ideal audience ooit bestaan?

SHANA: I wrote Ougat for everyone, to the benefit of the Coloured woman. I want our stories to reach the world and be seen as equally valid. So I would say I write for my people, to the rest of the world. I have been told that the experiences in Ougat are universal, and that realisation means something when it comes to empathy for each other, as women. I haven’t fully figured it out yet, but there is something there.

My blog was different stories from my past — some made it into the final edit of Ougat, but it was also social commentary about what was current at the time, and how it affected women. I wanted Ougat to be a more chronological, focused piece on things in my life particularly related to being a Coloured female who grew up in the 90’s and early 2000’s.

After Ougat, my audience certainly did grow (as in people who are now familiar with and interested in my work), but my target audience didn’t necessarily change. I still have the same target, everyone.

I sat in the toilet, staring at the pregnancy test, mostly confused by how I had fallen so far down the social ladder so quickly. The sex I had wasn’t even worth the trouble I was in. [...] I do remember it was a Sunday and that I was getting ready to go to church. If this were a text I would type LOL. [...] I was dating a boy I didn’t even like, because his bossy, obnoxious sister was my only friend at work. And for good measure, to really give my mother that heart attack, he was Muslim. I was a Catholic, Coloured 20-year-old, who was pregnant by a 19-year-old Muslim call centre worker I didn’t like. I was for all intents and purposes, binne in my poes. [Hoofstuk 7, ‘The end of my lyf’]

VERONIQUE: ’n Memoir is natuurlik baie persoonlik. ’n Mens kan sort of niks sugarcoat nie. Was jy at all innie process bewus, bekommerd of ashes oor hoe jy perceive sal wôd ná die publication van jou storie?

SHANA: LOL “ashes”. I always joke that I can’t be embarrassed because I have no self-respect to begin with — it seems self-deprecating but it is somewhat true. I think I was degraded so much as a child and young woman that I stopped caring about my own gevriet. I became comfortable with having no secrets. I wrote everything with purposeful honesty, particularly explaining the ugly and humiliating and gruesome parts as is — not exaggerated, but not made palatable.

VERONIQUE: Expectation is ’n groot theme in jou memoir. Jy spreek tot die idea van ’n respectable Coloured woman. Enige advice vi girls wat hie’deu gaan?

SHANA: I love this question: A respectable female is a myth. We are all worthy of basic respect, regardless of the life we choose. Respectability is an unreachable, maddening standard put in place by men who want to control the narrative of a “lady”. Additionally, being a respectable Coloured woman has always been sold as being as un-Coloured as you can — sound refined and English, straighten your hair, speak quietly and pretend you don’t have fire in your throat and soul. My advice: Make yourself happy. Tell them to go fuck themselves.

VERONIQUE: Jy gesels vrylik oor shame innie boek. My ma het vi my gehad toe sy 19 was en daa het oek ’n groot, donker wolk vol shame oor haa kop gehang. Soe ek kan relate mettie unavailable waiting room to express en cipher-through van shame, al issit vanaf ’n external point of view. Daa issie regtig baie safe spaces vi vroue om honestly hieroor te praat nie. Dink jy die safe space rondom hierdie shame bestaan buite die ruimte van social media of issie spaces maa nog steeds limited en agterie skerms?

SHANA: We need more space, but there are more than we used to have. The thing is this new “wokeness and acceptance” is but a small percentage of the real, offline world (and very much a movement by the new generations). Us millennials are still caught between wanting to break free and the bullshit, guilt-fuelled conditioning of our parents and “what will the people say” rhetoric. Everyone should be a safe space. Everyone should have a safe space.

A lesser-known fact about me, to my family at least, is that I am bisexual. Mostly gay. Yes, I am married to a man. [Hoofstuk 4, ‘…and women’]

VERONIQUE: Die sexual shame wat gepaard gaan mettie discovery van ’n vrou se sexual freedom en needs is iets wat steeds noggie genoeg bespreek wôd nie. Issit grootliks omdat daai shame van generasie na generasie oorgedra wôd en nie directly mettie shame-causers address wôd nie? A.k.a. patriarchy, a.k.a. are you jas.

SHANA: LOL. People need to come to terms with the fact that women like sex. And yes, it is generational shame, but it isn’t real — sex isn’t shameful. Rape is shameful. Not caring for consent is shameful. Enjoying sex is liberating and human. The shamers think sex is dirty but they also enjoy it. We don’t teach safe and proper enjoyable, consensual sex to our kids and end up with a new perverted, shameful, stupid generation and start the cycle all over again.

VERONIQUE: Innie boek tackle jy stories wat baie vroue experience en mee kan relate, maa nooit oor kan of wil praat nie. Was dit jou intention om sort of ’n CPR-like piece voort te sit wat nuwe lewe innie vrou wat similar experiences het, te blaas?

SHANA: Yes. I want women to know that they aren’t alone in their experiences and don’t have to feel shame. I will be the fall guy and take the public embarrassment if it means a woman out there feels less isolated and humiliated. Abusive men use shame to control their victims, to keep them in line. You take away the shame, you take away the shackle.

“I want women to know that they aren’t alone in their experiences and don’t have to feel shame. I will be the fall guy and take the public embarrassment if it means a woman out there feels less isolated and humiliated. Abusive men use shame to control their victims, to keep them in line. You take away the shame, you take away the shackle.”

VERONIQUE: Met elke body of work wat ôs as writers produce, is daa tog creative techniques wat mens moet toepas om die waarheid en die complexity vannie lewe te depict oppie bladsy. Wat sou jy sê was daai creative tools en techniques vi jou?

SHANA: I wrote it in my language — Kaaps. That kept my storytelling authentic. That was my only creative technique, if it can even be called that.

VERONIQUE: Innie memoir moet jy heeltyd memories recall. Issit at all exhausting om heeltyd jou pyn, joy, confusion en history te relive noudat dit getik en gedruk is? Veral in terme van 20-year-old Shana.

SHANA: It was humiliating. LOL. I see her as external to myself. I don’t recognise her thoughts and feelings anymore. And watching her objectively made me feel secondhand embarrassment. But I also developed an empathy for her. She wasn’t aware, self-aware, anything-aware.

VERONIQUE: Hoe het jy opgekô mettie titel?

SHANA: It just came to me. It is a word I have heard my whole life, literally since I was a toddler. And when it came to mind, I just knew that was the one.

VERONIQUE: Die colours vannie cover is jas en kak catchy. Wat wassie inspiration agterie voorblad en die illustration van Ougat?

SHANA: Aimee and the designers felt that using my face was best, the me now — we played around with the idea of using an image from my past, but then settled on the current imagery. I chose orange because I didn’t want to use pink. Orange feels strong and bold.

Afshowerag — adjective: show-off

Bymekaar — together (as in a couple); also, to hook up

Gran — to like

Los kin — a sexually loose woman, a whore

Ougat — a precocious child, old-fashioned, to have sexual inclinations

Permy — always

Poes — vagina

Tollie — penis

Yous — you guys

[Enkele voorbeelde uit ‘Glossary’]

VERONIQUE: Hoekô wassit belangrik vi jou om ’n glossary agterin te add?

SHANA: Not all Coloureds have the same slang, or use the same slang words in the same way. We didn’t want anyone to get lost in translation.

Eerste en oudste Afrikaanse tydskrif, sedert 1896

Ons bou aan ’n moderne beeld van hoe Afrikaanswees lyk, lees en klink. Het jy van Shana Fife se memoir virrie benefit van Coloured women gehou? Dan ondersteun ons. Vriende van Klyntji word op hierdie bladsy gelys.