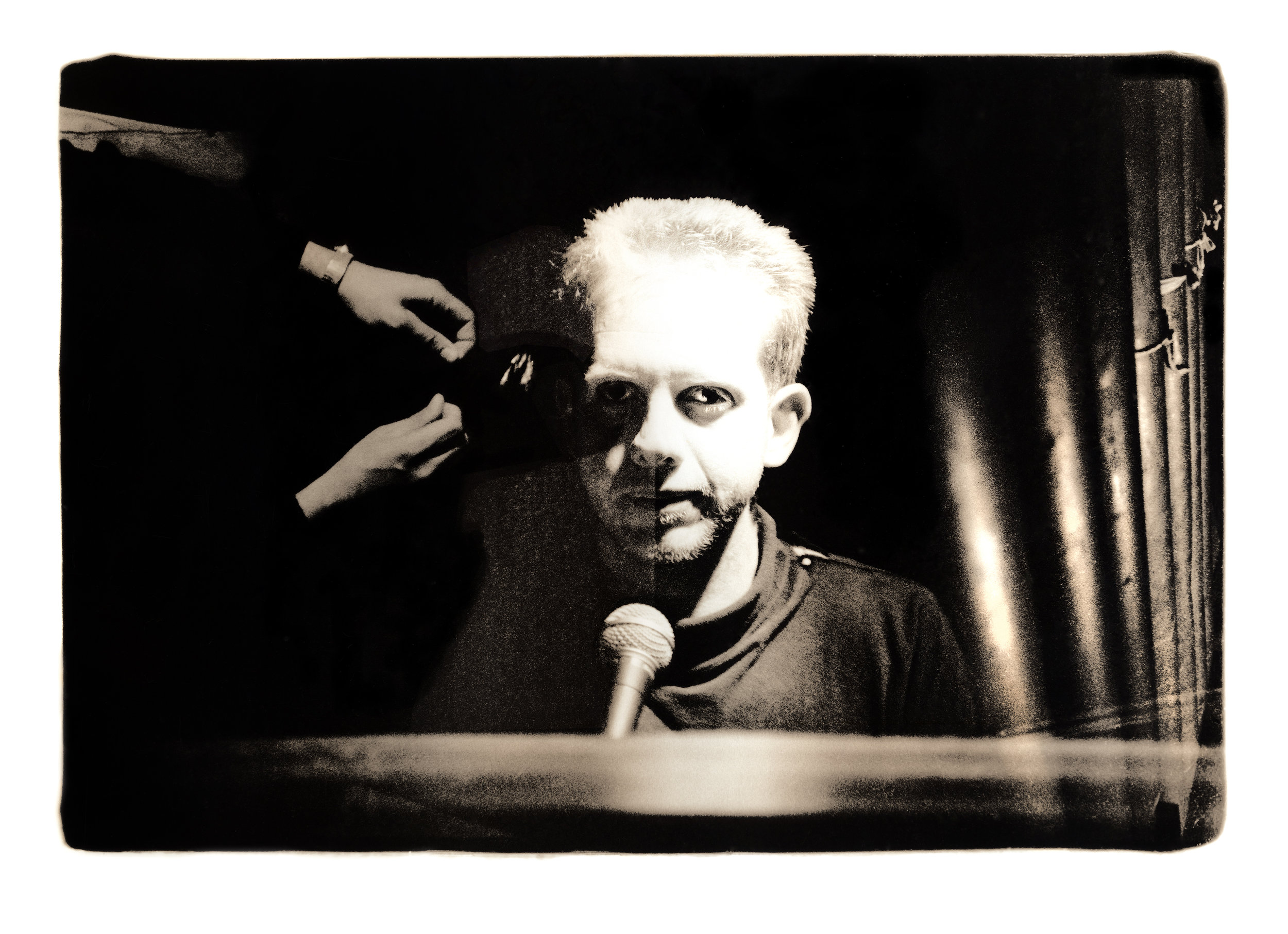

'n Onderhoud met 'Die Stropers' se regisseur Etienne Kallos

Hy praat oor grond, erfenis, geloof, manlikheid en kultuur

Die Stropers se debuutvertoning het onlangs by die Cannes-filmfees plaasgevind en is goed ontvang. Die film speel af in die Vrystaat, 'n geïsoleerde vesting vir ’n Afrikaanse etniese minderheidskultuur. In hierdie konserwatiewe boerderygebied is daar ’n obsessie met krag en manlikheid, maar Janno is anders. Hy is geheimsinnig en emotief. Eendag bring sy hoogs-godsdienstige ma vir Pieter huis toe, ’n verharde straatkind wat sy wil aanneem. Sy vra vir Janno om hierdie vreemdeling sy broer te maak. ’n Stryd om mag, erfenis en ouerlike liefde ontaard egter tussen die twee seuns. Klyntji publiseer ’n ope-onderhoud met die regisseur Etienne Kalos.

Could you tell us a little about your background prior to this feature debut?

I am a Greek-South African from Cape Town and my first love was theatre, I did my Bachelors in playwriting and stage design. This is where I met a mentor who changed my path: the Afrikaans playwright Reza de Wet. She wrote in Afrikaans, the language of Afrikaners, the descendants of the first Dutch settlers who arrived in South Africa in the 17th and 18th centuries. ‘Afrikaner’ is the old Dutch word for ‘African’. Reza is probably the most translated Afrikaans playwright in the world. I first attended her class when I was 17 years old. Her plays showed me new ways to explore the South African experience, especially in the post-colonial era. Her work isn’t political, but rather mythological, some might say it’s gothic. She’s the one who first told me about the eastern Free State, the region where The Harvesters was born as a project. We shot between Free State and KwaZulu-Natal, the bordering region which is the only one to have funded the film.

Your short film, Firstborn, which won the Golden Lion at the 2009 Venice Film Festival, was inspired by one of her plays.

Yes indeed. I was doing my graduate studies in film at New York University. I hadn’t spoken to Reza de Wet in many years. But I wanted to shoot my graduation film in South Africa, so I got back in touch with her and we worked together on the script of my short film, Firstborn. I am a teacher now myself and so it meant a lot to me, to come full circle and work with my first mentor again after so many years. Later she gave me feedback on an early version of The Harvesters script before she passed away in 2012. The Harvesters somehow continues the work we had started with Firstborn. Except that the 30 minute film featured incest, matricide, a protagonist who goes mad and was inspired by one of Reza’s plays. I next wanted to find out what would happen if I removed those spectacular elements and wrote something original in a feature length format.

What is so special about the Free State?

It is a fascinating region, the “bible belt” of South Africa, all maize fields, farmhouses and church steeples, it’s the heart of Afrikaner culture. The eastern part of the region is especially intriguing, it is wilder than the western region, there is something mysterious and powerful in the landscape, something that captures you and won’t let go.

Set in the middle of nowhere, these farms could be heavenly places, yet there are bars on windows, there is fear in the air. Hearing about farmers being murdered is not uncommon. A political notion that is becoming popular is that the government should take the farms away from the Afrikaners to the benefit of the black population. Could or should this be done? I don’t know but it brings up fascinating notions of what it means to ‘belong’.

What is your perception of that population?

I respect the way the Afrikaners work the land, they are devoted to it. And I like the new generation. I wanted to explore adolescence and tell a story about the first generation to be born completely outside of the Apartheid system. The issue of this legacy is never addressed directly in the film, yet it is all-pervasive, through the feeling of alienation of the young protagonist, Janno, through his loneliness, his fear of being judged, how lost he feels: How do you live with the weight of post-colonialism on your shoulders? Do we have to literally and figuratively burn the structures of our ancestors to become African? This is my experience too, the fracture inherent in being an African of European descent. The experience of fracture is an important issue for me, to love and hate in the same breath, to belong and feel like a stranger at the same time: you grow up oblivious and then, suddenly, as a teenager, you realise that you don’t really belong in your family, in your community, in your culture. It is a universal experience, this loss of childhood, but I wanted to give it a rural setting, because when you live in a city you dominate space, whereas in the countryside, it’s the other way around: the land and the elements control you. The silence of the countryside exaggerates every decision you make, every action you take and throws it back at you.

How was the writing process?

I used research trips as a starting point. In 2010, I rented a car and just Drove around the Free State and KwaZulu-Natal, meeting people - farmers, orphans, high school students, social workers. The first draft was a combination of research materials, it was just too broad and realistic, I had to find a single thread to tug. I started a second draft after I had returned and was teaching in the USA, it was based on a scene I came up with: a farmers’ son walks into the kitchen at night, he sees his mother and aunt praying; they are praying for him, but without looking at him. It is as if he is not really there, as if he is invisible. As they pray they say that there is another boy in the next room and that he must love this boy and open his heart to him, make this new boy, this stranger, into his brother. And just like that, the foundations of the film were laid, everything was already in that scene: the main characters, the newcomer as a threatening double, something magical or unreal in the atmosphere. I didn’t want a realistic film, but rather an inner journey.

Religion was already present in that founding scene...

Religion is present in all my work and the Afrikaners are one of the most churchgoing people in the world. Living in isolation on farms, religion keeps them company. The idea of prayers, the act of praying, the presence or absence of God and the idea of the Last Judgement are all fascinating to me. This means, of course, that I am a big fan of Bergman films.

Where is this story about two enemy brothers coming from?

Like I said, I’m a fractured person, split in two and I explored this experience through the dynamic between Janno and Pieter. I wrote the characters as two parts of one soul, split into warring factions, love and hate mingled together, locked into an eternal and unwinnable dance for domination. For me this kind of ‘brotherhood’ cannot be described sufficiently in words but it is exciting to dramatise. Despite the socio-political context, this is not a story that occurs in the exterior world. There is a tension between interior and exterior worlds that is very exciting to work with cinematically.

How did you move on to production?

So I wrote a second draft, which I sent simultaneously to the Cannes Cinéfondation Residence program and to the Sundance Screenwriting Lab. In 2012, both programs luckily selected my script, so I travelled from Paris to Utah. And the script was awarded twice: it received the Gan Foundation’s Prix Opening Shot Prize for best screenplay at Cannes and the Mahindra Global Filmmaker Award at Sundance.

What happened next?

With these two prizes and a Golden Lion for Best Short Film, I thought my first feature film would be easy to finance. But it wasn’t the case.

I kept on travelling and researching, establishing connections with generous farmers – the harvest sequence, for instance, was literally a gift from a farmer who gave us his maize crops, trucks and threshers for a day. I only got this film made through the generosity of the Afrikaans people. I would drive around at random and knock on farmers’ doors. Sometimes I would literally dream of a farmhouse and then I would wake up and drive around trying to find it.

In the end, a South African producer brought a Canadian producer on board, who in turn brought on board Sophie Erbs, from the French company Cinéma Defacto, to co-produce the film. The first two partners dropped the project, but the good relations I had built with Sophie allowed us to make the film together. She hasn’t stopped fighting for the film since I met her, that was six years ago.

How did you find the two boys who play Janno and Pieter?

I wanted them to be really 14 or 15, an age when emotions still shape bodies. Kids of that age grow up fast, so I postponed the casting for as long as I could. Afrikaner society is quite conservative, so it wasn’t easy to gain access as the script explores, in part, sexuality. Half the schools refused to allow me to hold auditions... But I also met youths and their parents who were unbelievable and believed in me and this project. It was just ten days before my shoot when I finally cast the two young actors. I knew there had to be a lot of chemistry between them, and that such chemistry would come, in part, from their contrasting personalities.

I thought that the character of Janno should be physically fragile, that he should give the impression of not being able to cope with the demands of farm life. But Brent, who plays the part, is quite the opposite - he is a high school wrestler and rugby player - from the first audition I knew that it would be him: I could sense under his reserved demeanour a frenetic emotional quality, something unspoken and inspiring, and more importantly that it didn’t scare him to explore such a secret part of his inner life. He had the underlying emotional strength required for the part.

Then I found Alex, who plays Pieter. He had just turned 14 and had no acting experience whatsoever. In contrast to Brent, who is more urban with his love of hip-hop and Kanye West, Alex comes from a family of farmers from the Cape Town area. He has a natural charisma that the camera loves and whereas Brent’s freneticism feels emotional and subterranean with Alex it’s all extroverted and physical. They were a great match.

Has Pieter been adopted by the family to replace Janno?

It is what Janno thinks. My job was to bring to light his fears, his own perspective, to explore the limits of a single point of view. What his parents actually think or do isn’t what the film is about. Janno hears whispers, insinuations, remote conversations and then extrapolates, his opinion is based on those snatches. Janno craves unconditional love, and his parents have difficulty expressing their love. But it doesn’t mean that they don’t love him, perhaps even unconditionally. I just really thought that the story had to remain ambiguous, especially as it’s about a young person who does not know good from evil yet. The music, for instance, should never convey joy or sadness, it had to strike a balance, so that the audience could participate in the story, have a full experience and form their own conclusions. Pieter isn’t some lost city child who finds redemption through his contact with nature. Speaking of redemption would imply a judgement of the characters, you must sin in order to be redeemed and I don’t judge them like that.

Tell us about that photo gallery which Janno contemplates so often.

I found all remote farmhouses from the region have that kind of family portrait gallery on the walls, it is a refrain from loneliness, a comfort. Every farmer wants to look up and feel that his family has been there for three centuries. It is a way of saying “we belong to this land, look at all the souls who came before us...” Which community do I belong to? Which land do I belong to? These questions form part of the main themes in the film. Today, not to belong to a place or community is a common thing, as we hear and read everyday about stories of immigrants, refugees and exiles. As the South African government mulls over the idea of telling the Afrikaners that they don’t belong there, that they should give back their land, it shows that the very idea of belonging is evolving and that is part of the story. As for Janno, the pictures on the wall are not a comfort, they are a weight against which he pushes. He is moving towards a new Africa, a new sense of place that has not been discovered by the older generations.

How did you work on the image of the film?

I lured Michal Englert, a fantastic Polish cinematographer, with photographs of the Free State that I had taken during my years of road trips. He came early to South Africa so that we could criss-cross the area together and brainstorm. I also watched a bunch of classic Polish films, some of them with religious motifs, like Jerzy Kawalerowicz’s Mother Joan of the Angels, so that I could understand his cultural point of view. Before the shoot we made a shot list and storyboarded some scenes. I didn’t want the image to transform the landscapes – they are already unique and beautiful, for instance it was always a dream of mine to shoot at Sterkfontein Dam, the artificial lake where we staged the rugby and fishing scenes. Michal is also so great at hand-held camera work, so we begin with static shots and gradually transform into hand-held as Janno shifts and unravels and finally the film returns to static frames as a way of coming full circle. The nightclub scene is amazing, it offers a kind of dreamlike breathing space... I see it as almost the future of South Africa: On my travels I was surprised to find that every farm town on the border between Free State and KwaZulu-Natal had a small Chinatown area, immigrants coming in through neighbouring Lesotho. They don’t care to speak English or try to be white, but rather speak Zulu or Sotho. A ‘shebeen’ is an African nightclub and I thought how great it would be to create a ‘Chinese shebeen’, they don’t exist yet but they will. Yes, the scene has a dreamlike feel, but to me the whole film is dreamlike, like a feverish chamber play. Or, say, cathartic.

Like a Greek tragedy?

Yes, a few years ago I visited the island of Rhodes with my mother, and attended a live performance of a Greek tragedy for the first time. It was Iphigenia in Tauris. I was struck by the intensity of the acting, Iphigenia came onto stage crying and was hysterical from start to finish! That Greek style of sustained intensity is very exciting to me, it impacted how I chose to tell the story of The Harvesters. Still, at heart I am African and so I always knew I had to make my first feature film in my country, to make a film in South Africa about South Africa, even though the next will probably take place in the United States, where I live now.

Eerste en oudste Afrikaanse tydskrif, sedert 1896

Ons bou aan ’n moderne beeld van hoe Afrikaanswees lyk, lees en klink. Het jy van 'n Onderhoud met 'Die Stropers' se regisseur Etienne Kallos gehou? Dan ondersteun ons. Vriende van Klyntji word op hierdie bladsy gelys.